Halloween is an odd time of year, when people who never normally watch horror movies or read ghost stories seem to find an excuse to do so. The webpage of a national newspaper might discuss a short story by

Robert Aickman, and a respectable broadcaster might devote an hour to an informed discussion of

European horror films.

I'm probably guilty on this blog of discussing the more obscure aspects of horror fiction, at the expense of commercial books that a wider audience will have heard of. So in tribute to Halloween and the temporary mass celebration of all things scary, I've decided to do a post on my favourite BIG horror best-sellers. These were the kind of books that introduced me to the genre when I was a teenager and it’s unlikely I’d be reading Aickman & Co. if I’d not read the likes of King and Simmons first.

I've imposed some strict rules on my selections here: no tricksy post-modernism (sorry, House Of Leaves); no psychological ambiguity (bye bye Turn of The Screw and Hill House); nothing old (stop moaning, Doctor Jekyll And Mister Hyde) and no short stories or novellas (adiós just about every weird, under-appreciated book I've ever featured here). Instead, these are the block-busters. The writers of cracking action scenes with unambiguously evil villains. At least three have been made into movies, and the other two should be.

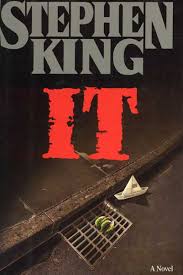

I guess it’s obvious from the above that this list would include King, so I thought I might as well start with him. IT is probably my favourites of his horror novels, and it exemplifies the kind of book I'm talking about here: vast, with a sprawling cast of characters, and a ‘big bad’ who has been responsible for decades of fear in the Maine town (of course) of Derry. The story takes place across two timelines – the characters repeat scenes from their childhood as flawed and weaker adults… King’s handling of this, and the creepy effects associated with time repeating itself, are a highlight of the novel and really call into question those people who think he can’t write with any subtlety. (Just because the books I'm talking about here are big bulky blockbusters doesn't mean they’re big bulky dumb blockbusters.)

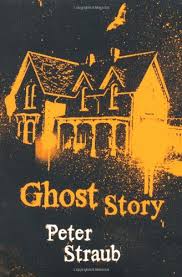

For me, Ghost Story is Straub’s best book by a country mile – forget the singular title, this book should really be called Ghost Stories, containing as it does multiple stories told by a group of old men know as the ‘Chowder Society’. Straub takes the Stephen King approach of using an American small town as a setting for his horrors, and as a microcosm of society as a whole, but this is distinctly his own style. As the story progresses it becomes clear that each of the individual ghosts and monsters are just facets of the real evil; that each of the separate stories being told, are in fact just elements of one story after all.

Probably the most ‘arty’ book in this list, and arguably not horror, being told as it is from the point of view of a monster. But there are bigger monsters in this tale than the vampire doing the talking, and the real horror may be the slow falling away of his humanity… I like this book for it’s lavish set pieces (the whole book is nothing more than a series of set pieces, really) and the darkly luxurious feel of the prose, particularly in its descriptions of night-time New Orleans and Paris. Maybe this was the start of the trend towards Twilight and everything bad associated with that, but here the vampires still have a decadent, almost nihilistic edge. (Everything else I've read by Rice, including the sequels to this, I've not liked at all.)

An absolute whopper of a book, which has a premise that makes it sound like the worst tripe imaginable: ‘mind vampires’ have been controlling human affairs for decades. But this was back when Simmons was at the top of his game (by contrast his last book was one part plot to nine parts Tea Party ranting) and he plays the idea of mind vampires with a completely straight bat. They become almost the ultimate villain, responsible for humanity’s evils both big and small. And like all the best villains they are completely compelling. The odds seem ridiculously stacked against the human heroes and despite the simple good versus evil plot, the book has an air of desperation in places that makes it stand out.

The most recent book on the list and yet another one about vampires. I don’t know if Lindqvist has read Interview With The Vampire, but given it’s English-language ubiquity it at least seems likely he might have. One of the minor characters in that book might have been the inspiration for this one – a child vampire. A creature that has lived for centuries but still has the body of a kid. In some ways this is the darkest of the books in this list, with its setting of an 80s Swedish housing estate, and its background themes of addiction and child-abuse. In this setting the child-vampire is only partly horrific, and the tale of her relationship with a lonely schoolboy has a real emotional core, twisted and bleak, but there. The kind of book that gives best-sellers a good name.

Feel free to mention your own big bulky favourite horror novels in the comments...